A sequel that takes the thrilling cold-survival city-building heart of Frostpunk and evolves it in every way, while losing none of what made the series so special to begin with.

Frostpunk remains one of the most thrilling city-building games I’ve ever played, a tense and hard-fought scramble for survival at the frozen end of the world. A Dickensian tale, almost – a Victorian fable choked in smog and despair as children are sent to work in factories and the dead are eaten, all in the name of survival. There’s no room for sunshine; an apocalyptic storm is coming that will plummet temperatures below 100 degrees celsius. There’s no room for dissent; crush it – or else the world will crush you.

I worried the sequel would jeopardise that by swamping it in complexity and an urge to do more, to go bigger, to be better – to be a sequel, in other words. And developer 11 bit didn’t assuage my fears by talking about squabbling political factions being the focus of the game, which sounded about as much fun as watching Prime Minister’s Questions to me. I worried 11 bit would overcomplicate it and lose the thrilling essence of what Frostpunk once was. But it hasn’t.

Frostpunk 2 has managed the remarkable; it’s managed to grow in every direction and dwarf the original while still retaining the breathless experience of playing it – that inescapable sense of clinging on. I don’t think I breathed at all over the five chapters and 17-odd hours the story took me, which, come to think of it, is a long time to hold one’s breath.

Moreover, it’s gotten bigger without getting flabbier. By jettisoning a whole bottom layer of micromanagement it no longer needs, and letting you govern in broader strokes, Frostpunk 2 has done away with enormous amounts of faff and freed you up to think about more interesting things. And it’s all honed almost to perfection: though it seems more complex, I never found myself at a loss about what to do, or very confused, which I believe signals a developer that has learnt an incredible amount from its first game and then gone to great lengths to show it. Frostpunk 2, in so many ways, is exquisite.

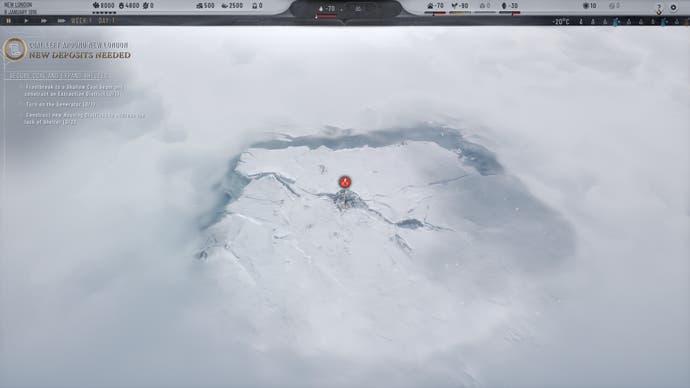

But let’s break it down a little. The biggest change between the two games is conceptual: in Frostpunk 1, you were a band of a few survivors establishing the last city on a frozen Earth, fighting each day to keep it and yourselves alive – collecting armfuls of coal from the nearby snow, dragging fallen trees into your settlement to chop up for wood. Gradually, something like a city emerged, and eventually you’d pit it against a huge storm, forever answering the game’s overarching question of can you survive? But in Frostpunk 2 it’s different. The question is not whether you can survive but how. It’s zoomed out. Day to day survival is a given, more or less – the cold is still a fundamental terror – and you’ll control cities that are incomparably larger than the ones you finished the first games with.

Everything about Frostpunk 2 is on a larger scale. It plays in weeks and counts people (and their deaths) in their hundreds and thousands, and harvests huge quantities of resources in order to cope with them. Cities are built not building by building but district by district, allowing you to slap them down in bulk and expand much more easily, and to manage them more easily too. You’ll have housing neighbourhoods and industrial zones, and resource-harvesting areas which can suck up multiple resource nodes at once. You can expand them all, too, to take in more area and to allow space for more special, resourced buildings in them. It’s a much neater and quicker way to build a city, and a much less daunting way to control it at size. Should you want to adjust the amount of power a district draws during a moment of especially cold weather, for example, you can simply move a slider around until it lands on the input-output sweet-spot you’re after. That means you’re adjusting only several things over the entire settlement, which is much easier than selecting individual buildings and tweaking them that way.

On top of that, you no longer need to build roads or any transport links, save routes you establish in the frozen tundra beyond, and it’s an enormous help. All transport infrastructure in your settlement is automatically taken care of and will appear whenever you plonk new districts down. It saves a great deal of time and means you can focus more on the careful political balance within.

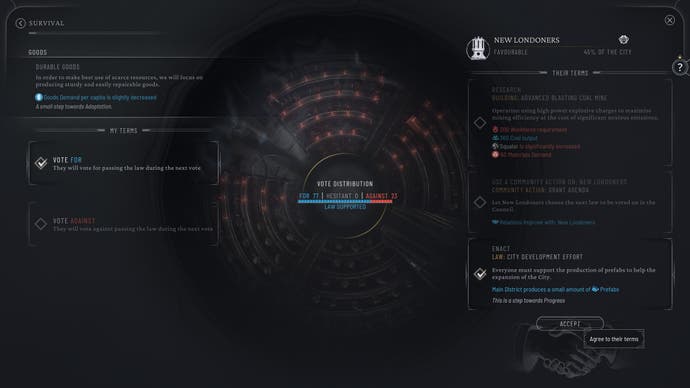

Political factions can ruin you if maltreated, staging protests across your city and shutting down districts if things get really bad, putting incredible strain on your settlement – just like strikes in real-life, I suppose. The factions are a bit like that, the unions of society, only amped up considerably for dramatic effect. There are a lot of them – many more than I encountered during my campaign – but the ones I interacted with were the Frostlanders, Pilgrims, Stalwarts and New Londoners, and each believed in their own, often contradictory thing.

Frostlanders, for instance, believed in being at one with the frozen wastes, so favoured adaptation, whereas Stalwarts were all about mechanical progress. They clashed frequently. But there is no making everyone happy in Frostpunk 2; whatever you do, you’ll find yourself like a tennis ball batted around a court, desperately trying to appease different sides as you work towards a larger goal.

More often than not, appeasing involves passing a law, and here’s where another of the game’s new features come into play: the Council chamber. It’s a building you can see inside, for the first time in the series – there is a chamber with people milling around in it – and it’s here where you’ll try to pass your laws. I say try because you’ll need a majority vote in order to pass a ruling, and getting a majority tends to involve negotiating with other factions to get them on side. And what they will want in return varies: perhaps they will want a law passed in return, or a building researched and built, or for you to fund them. You’ll be looking for something that aligns with your values, naturally, but Frostpunk 2 has been designed in such a way that this isn’t always possible, and typically you’ll be under so much pressure you won’t have any option but to acquiesce.

This all sounds quite complicated but actually, it isn’t, and this surprised me. Like nearly everything in the game, it’s very clearly signposted. A faction will ask for something and then flashing indicators will point where you need to go and signal what you need to do. All you need to do is see it through – unavoidably making more promises in the process. So the wheel of Frostpunk 2 turns, one promise for another, around and around, until you either fail to make good on a promise in the allotted time frame, or you make a calculated decision to ditch it in order to pursue a more pressing issue. And there’s always something more pressing at hand.

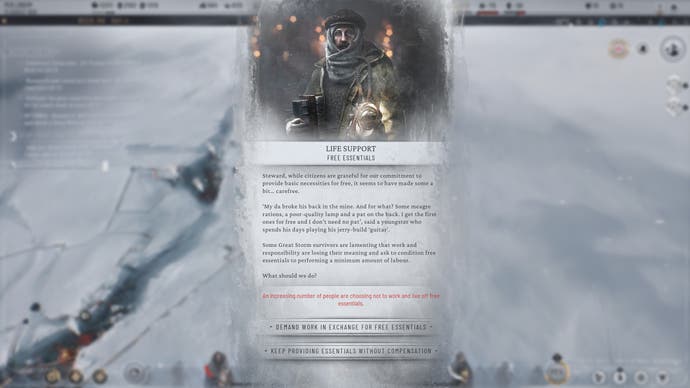

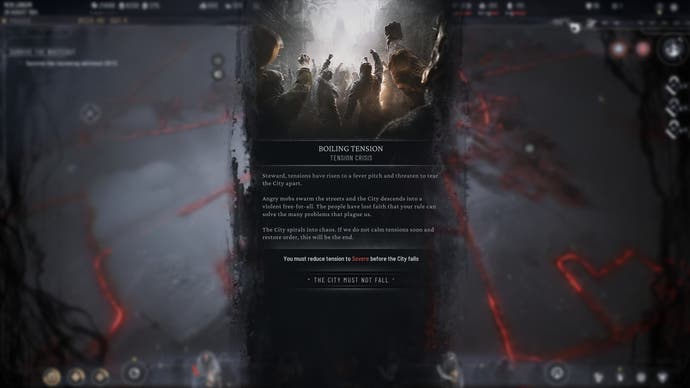

Tension runs high in Frostpunk 2, literally in the sense that there’s a tension gauge that fills to represent discontent in the city, but also because there are many other gauges to keep an eye on. There’s crime, disease, squalor, as well as cold and hunger, and there’s also the trust of your people and relations with individual factions to consider. These are the many spinning plates the game asks you to keep up, all as it tightens the screws and throws, say, severe cold patches at you, or thrusts population growth on you, or foists you with some other extraordinary occurrence. Always, there’s something you’re in dire need of doing, especially in the main storied campaign. It never lets you be, never lets you get comfortable, and that’s how you find yourself in the Council chamber one day contemplating human experimentation. For real. I would never have passed that law normally (obviously!) but Frostpunk 2 – like Frostpunk 1 before it – finds a way to make the horrific plausible, and that’s where its special sauce lies.

Frostpunk 1 tried to tempt you with dictatorial, totalitarian power – that was its big theme. It pushed you into a position where you couldn’t cope and then dangled an incredibly unsavoury way out before you, which I’m ashamed to say I took. It’s similar in Frostpunk 2, although it isn’t as preoccupied with dictatorial rule (it’s still there, just less pronounced) but with extreme elements in our societies instead.

For instance, the Pilgrims: I thought they seemed quite egalitarian at first, suggesting welfare and a kind of communal existence, so when they came to me with a proposal about motherhood, which stipulated mothers wouldn’t work but would stay home to raise their children, I thought it sounded OK in the scheme of things – the scheme of things being freezing in the cold or getting mangled by machine attendants in factories – so I enabled it. Weeks later, I heard over the tannoy that, “Any mothers out in public, without a child, will be questioned,” and I began to have second thoughts. Then, the Pilgrims backed a father who wanted to stifle a mothers’ creative writing and burn her work because she shouldn’t be doing that. Then came a proposal for mandatory marriage. The Pilgrims were turning out to be wronguns. The problem was that by then their numbers had risen so much, with my support, that they weren’t easy to ignore, so I was in a pickle. And it’s the same for all the factions: they each have unsavoury elements to them, so whoever you side with, it won’t be easy.

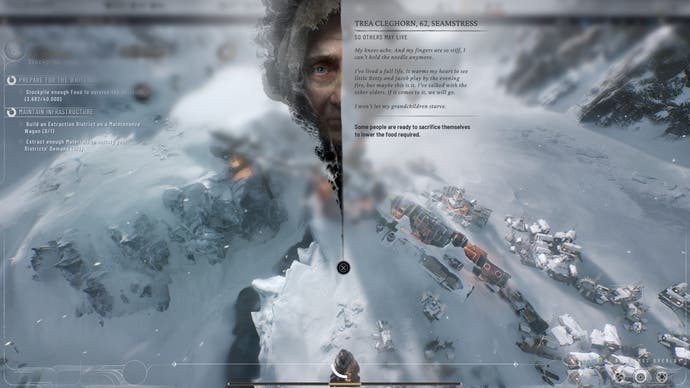

What I really like about the factions, though, is how they provide a more mechanical and game-affecting response to decisions you make than was there in Frostpunk 1. In the first game, a lot of the consequences were left to your conscience, for you to reflect upon and decide whether you were happy with. That happens here too – I was standing in a crowd yesterday waiting for a train, and I was reminded sharply of how I’d sent crowds just like this to their deaths to mine resources before a settlement imploded – and there are reactions from civilians to underline the things you’ve done. Remember that mother whose creative writing was in question? I ruled that she be able to keep writing, because it’s the decent thing to do, but weeks later I got a pop-up telling me she’d been killed for it. There are lots of moments like this in the game, moments that wind you slightly, that make you think. It’s part of the essence of Frostpunk. But the factional responses add something extra, something hard-coded, something you can’t help but contend with or else the balance you’ve established will be ruined, and it’s a development I really like.

But there are moments when this sea of interlinking cause and effect and consequence can combine to be overwhelming, and whatever you seem to do, factions turn against you. It’s as though there’s too much in play; you try to fix one thing only to discover several more things you have to address first, or that link with it. Often what you have to do can feel like an insurmountable task and as though the game is constantly against you, which I suppose it is.

I realise that it’s in this pressure where Frostpunk 2’s proverbial diamonds are formed, and its hardest, most memorable decisions are made, but the issue is exacerbated by the story taking place in one major city, which means if you get yourself into a pickle and fail, it’s that pickle you’ll pick up from when you have to try again, so you’re already in a precarious position. Towards the end of the game, it took me several attempts to avert a disaster I was beginning to lose all hope of ever averting. There are valuable lessons learned during these moments of course – moments where you scour every aspect of your operation for any advantage you can find, any minor change you might make that can tip the balance in your favour – and in doing so you learn the deeper strategical minutiae of the game. And then when you ultimately prevail, you’ll flush with a warm sense of satisfaction because of the hard work you put into it. But as in keeping with the attritional tone of the game as this is, it wasn’t always fun.

Frostpunk 2 has a few kinks that can aggravate slightly, too. Much more of this game is spent outside your settlement exploring the tundra, and you can establish multiple minor settlements there too, meaning you’ll be running more than one. Most of this is handled beautifully: you can zoom in and out with the mouse wheel seamlessly, or click to teleport straight from the UI – how the interface manages to show everything you need, without needing any hidden menu screens and without having any clutter, is borderline miraculous. But there were occasional moments when Generators in other settlements turned off on me, or supply lines went all out of whack, as though the game were tripping itself up, and when you depend upon these things because of the careful balance you’re trying to keep, it can be frustrating. Some individual buildings can also be harder to pick out around districts, too, which is annoying in a pinch.

But overall, Frostpunk 2 is a triumph. Yes you lose some of the close-up feel of the original as the strategy zooms out – the burlap-wrapped civilian toiling in the cold or digging a snowy trench for others to get through – but Frostpunk 2 was never meant to replace that game. It was meant to lead on from it, and it does that superbly, with some wonderful nods to the original too. Anything it loses, it gains back via new features tenfold.

Visually, it’s spectacular. The way housing districts sprout like moss from the walls of deep crevasses is endlessly screenshot-able, and the way the screen darkens and the glow-trails of activity redden when tension rises is enormously dramatic. Coupled with the sweeping orchestral music of the industrial revolution, it all makes for an incredibly impactful package, and touches like the charismatic tannoy announcements – “Remember, all new products have been tested on convicts and are safe for use” – highlight a level of detail and reactivity not found in Frostpunk before.

Now, too, when the story finishes – which admittedly ended on an anticlimax given moments that preceded it – there’s an endless mode with half-a-dozen customisable scenarios to keep you playing on. If, that is, you don’t fancy playing the story again to achieve less of an unsavoury outcome. In every way it’s better; Frostpunk 2 is Frostpunk at its best and everything a sequel should be. Bravo.

A copy of Frostpunk 2 was provided for review by 11 bit Studios.